Reviewed by Lee Hill

In his 1946 essay, Politics and the English Language, George Orwell said: “…if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought. A bad usage can spread by tradition and imitation, even among people who should and do know better.” Clear thinking, common sense, open debate and reason face new threats from the grip that marketing, branding, spin, “fake news” and other forms of intellectual cheerleading now have over our lives. The extent to which this corruption can infect even the most progressive nations, organisations, communities and individuals is one of the many themes of The Square, Ruben Östlund’s problematic follow-up to his 2014 arthouse hit, Force Majeure.

At its best, The Square is a flip-flop version of Bicycle Thieves. Instead of a father and son struggling to survive unemployment and petty crime in post-WWII Rome, the focus is on Christian, a curator at a cutting-edge art museum in Stockholm. Christian is working closely with a trendy ad agency to promote a new exhibition, the all too literal installation that gives the film its title. Between the strategy meeting, where banalities are recast as miraculous insights, Christian’s iPhone is stolen by pickpockets (demonstrating more creativity than many of the artists in the museum).

A streetwise co-worker helps Christian track his iPhone to a social housing complex. At which point, a ploy not only to get the phone back, but obtain justice goes comically awry. In tandem with this storyline, Christian has an awkward one-night stand with an arts journalist, played with enigmatic menace by Elizabeth Moss, a visiting artist (Dominic West) with a surfeit of self-importance gets his comeuppance, and the museum itself, mutates from a citadel of free expression to a Potemkin Village of neo-liberal complacency under siege.

The first hour of The Square is an audacious satire of a high art establishment, particularly museums and galleries like the Tate or Museum of Modern Art, which rely on corporate sponsorships and wealthy donors to keep imperial schemes of bringing elite culture to the masses aloft. While the context seems specific, the hollow art speak is largely indistinguishable from the specious lingo (Corporate Social Responsibility, the oxymoron that excuses a multitude of modern sins, comes to mind), permeating many a modern workplace.

The dark comedy falls short of its mark in The Square’s second half as Östlund takes on sub-themes such as the refugee crisis, homelessness, the limits of democracy and free speech, trial by rolling news and social media, the sexual politics of dating, the sterility of urban architecture and even the ill-fitting uniforms chain store employees are forced to wear. This unwieldy ambition likely convinced the Cannes jury to award Östlund the Palme D’Or last spring over the Michel Haneke’s Happy End, which covers the same territory, but with a far more sustained, albeit chillier vision.

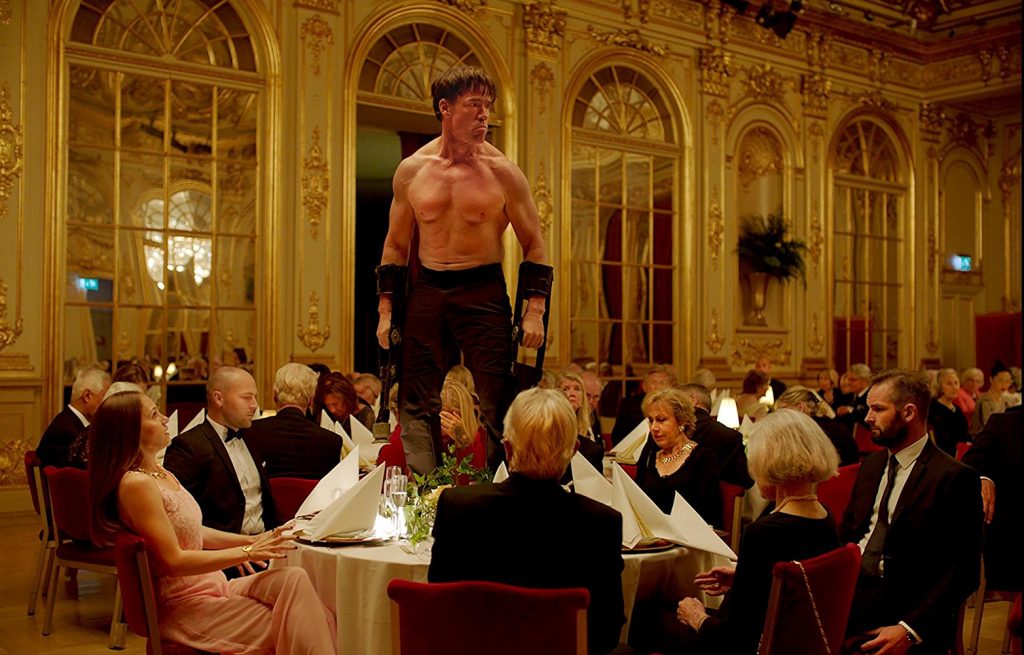

Despite The Square’s lop-sided anti-narrative, Östlund ’s flair for the bravura set-piece shines through, especially at a fundraising gala where a performance piece turns into a primal riot. Östlund also breathes life, thanks to deft casting, to types that might have descended into caricature. As Christian, Claes Bang is variously empathetic, creepy, vain, concerned, indifferent and all too hu-man.

If The Square has a single message, it is that many of us in the West are becoming like Christian; crippled by contradictory ideals and desires, speaking without communicating and acting without any common purpose.

Lee Hill is a freelance critic and author.