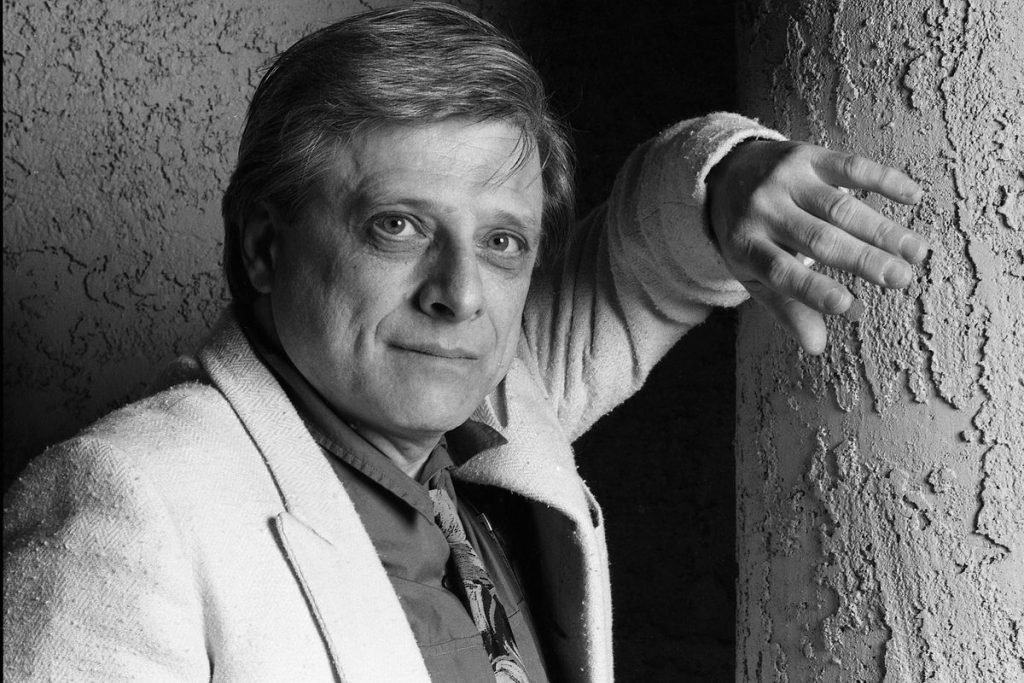

Harlan Ellison RIP: The Writer on the Edge of Forever

Essay by Lee Hill

Given that most of his books were out of print when he died, the widespread outpouring of love and admiration for Harlan Ellison belies the writer’s own cynicism about modern popular culture. During the heyday of his career in the 60s and 70s, Ellison dragged science fiction and fantasy (and legions of wallflower-like fans) kicking and screaming into the ferment of counter-cultural upheaval and experimentation. He did this not only as an award-winning short story writer, but through the anthology, Dangerous Visions, where he commissioned established and emerging writers, from Theodore Sturgeon and Robert Bloch to Samuel Delany and Philip K Dick, to explore themes such as sex, race, politics, the environment, the limits of technological progress, etc. with a revolutionary fervour that many in the parochial world of SF fandom were uncomfortable with.

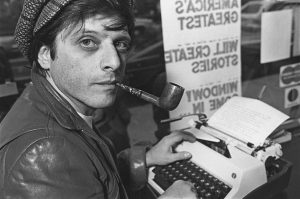

Dangerous Visions was a commercial and critical success boosted in part by Ellison’s unabashed fondness for self-promotion. His lectures and readings were akin to rock concerts thanks to a Lenny Bruce-like knack for satire and improvisation. He shook up the received ideas of the SF community in the same way Norman Mailer transgressed the norms of the New York literary establishment.

Although Ellison’s feature film career never really recovered from the disaster of The Oscar (1966), often cited as one of the worst films ever made, he wrote extensively for television. At a time when the Big 3 of CBS, ABC and NBC reigned, he often run afoul of meddling executives, network censors or directors who had difficulty setting a table for four let alone complex mise en scene. He wrote episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, The Man From Uncle, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, and most enduringly, “Demon With a Glass Hand” for Outer Limits (Ellison successfully sued James Cameron for appropriating the script as the basis for Terminator), and “The City on the Edge of Forever”, featuring Joan Collins, arguably never used better before or since, for Star Trek. Ellison was a pioneer in a medium that only saw writers as bait to get people to watch commercials.

In his take-no-prisoners TV and film criticism, The Glass Teat books and Harlan Ellison’s Watching, Ellison championed works that transcended formula and the expectations of genre. His contempt for the medium that paid for his California lifestyle made Neal Postman, author of Amusing Ourselves to Death, seem like Tony Robbins. Ellison decried the “auteur theory”, but lauded the work of Robert Altman, Francis Coppola and Michelangelo Antonioni and cited films like Seconds, Charly and Dune as favourite examples of fantastic cinema. He had little time for Star Wars and was particularly harsh on Gremlins (which is a shame since director Joe Dante has since revealed himself to be as subversive as Ellison in subsequent films).

In the 80s and 90s, as Ellison les enfant terrible, became the lion in winter, a generation of talents weaned on his books like The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World or Deathbird Stories gained the power and influence that eluded Ellison in his prime. Thanks to the likes of HBO and Showtime, American television made quantum leaps in ambition with series like The Wire and Sopranos leading the way. Even a Z-grade Star Wars rip-off, Battlestar Galactica, was rebooted for the small screen to become a potent allegory for the country’s post-9/11 mood. We now live in a digital landscape where the writer is king and speculative fictions abound in series as varied as Game of Thrones, The Handmaid’s Tale, The OA or Black Mirror.

Literary lives often contain unsolved mysteries that go to the grave with the author in question. In Ellison’s case, the mystery is why he never broke into the mainstream like Ray Bradbury, Roald Dahl, Kurt Vonnegut, Don DeLillo, William Gibson or John Collier – who he had more in common with than the Isaac Asimov or Arthur C Clarkes of the world. His friends included Robin Williams, William Friedkin (for whom he wrote several scripts) and Gay Talese. His love life, complete with five wives, arguably rivalled Warren Beatty’s. Granted Ellison made a lot of enemies, but he still made a better than average living as a fully paid up member of the Writers Guild of America. In a more just universe, Ellison should have been as big as Stephen King or George RR Martin or at the very least, as box set binge worthy as David Simon or Vince Gilligan.

When I was a pimply faced teenager of yore instead of the commute weary shambles of now, I was lucky enough to see Ellison in action at several readings and conventions. I had a tape of Ellison in peak form that I played nearly as often as my Monty Python and Beatle albums. At one Ellison event, he read an excerpt from, I Robot, a screenplay in progress, that was modelled on Citizen Kane (alas, a far less visionary adaptation was made with Will Smith many years later), talked at length about the philistinism of the average SF fan and passionately defended his deft boycotting of those US states that did not support the Equal Rights Amendment. I had and still own several signed editions of his work, particularly those with the wonderful covers and illustrations by his friends, the legendary Leo and Diane Dillion. In short, what little worldliness, taste and discernment I now possess as a grown-up, I owe in no small part to Ellison’s influence.

Yet all that raging against the dying of the light – a rage that was perhaps too much a part of Ellison’s persona instead of the empathy for the dreamers, lonely and damned shown in his fiction – never quite got him past the status of “cult writer”. Now I write that term in quotes, since everyone from acquired tastes like Henry Green and Jane Bowles to bestsellers like Hunter Thompson and Charles Bukowski, can fall into that vast universe. Ellison clearly made an impact, but was that impact anywhere close to the scale of his ambitions or output. Again, an enigma lingers.

In the last ten years or so, I found it hard to find either his new books (increasingly for small presses) or classics in quirky independent bookshops or motherships like Barnes and Noble. I got the palpable sense that Ellison had fallen off the radar of a new generation of SF fans, now plugged into everything from Japanese anime and China Mieville to the Marvel Universe and the annual orgy of millennial meta-branding that is ComicCon. And in fairness, I too was now overwhelmed by choice – Criterion DVDs, discovering obscure jazz and eurodisco on Spotify, landmark TV like Breaking Bad or grooving on the fact that a far more tender flower of the 60s like Richard Brautigan is now back in print big time.

Ellison’ s profile was not dissimilar to Gerald Hersh or Cornell Woolrich, the kind of baroque storytellers of the 30s, 40s and 50s, who perished or faded out when radio and magazines commissioned less original drama or fiction; writers whom Ellison would eulogise in his essays and recall as examples of how cruel fame can be to the writer. Like these ghostly scribes, I was barely starting to think about Ellison at all.

That is until he died in his sleep on the 28 June at the age of 84. And like so many fans, either going about their day or, if their dreams had come through, working on a new book or script, I was stopped in my tracks. And I was not alone. Others remembered Ellison in his many moods and for his many gifts to the popular imagination. They took in droves to social media to sing Ellison’s praises (and occasionally croak about his public excesses).

And of course, I not only remember Ellison and the vagaries of literary taste as well, but also remind myself that writers may die, but good work ultimately endures. As I did in the past to the renaissance of interest in Jim Thompson or Shirley Jackson, I look forward to Ellison’s work in reissues, adaptations and who knows, an addictive TV series or two. For those of you who don’t know Ellison at all – you are the lucky ones. Ellison Wonderland is still open for business.

Ellison was very fond of this quote by TE Lawrence : “All men dream, but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds, wake in the day to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act on their dreams with open eyes, to make them possible.” Various ministers of taste will debate what Harlan Ellison gave to the arts, but while he walked the Earth, he lived and breathed his dreams beyond measure.

Harlan Ellison born in Cleveland, Ohio on 27 May, 1934, died in Los Angeles, California on 28 June, 2018.