Reviewed by Lee Hill

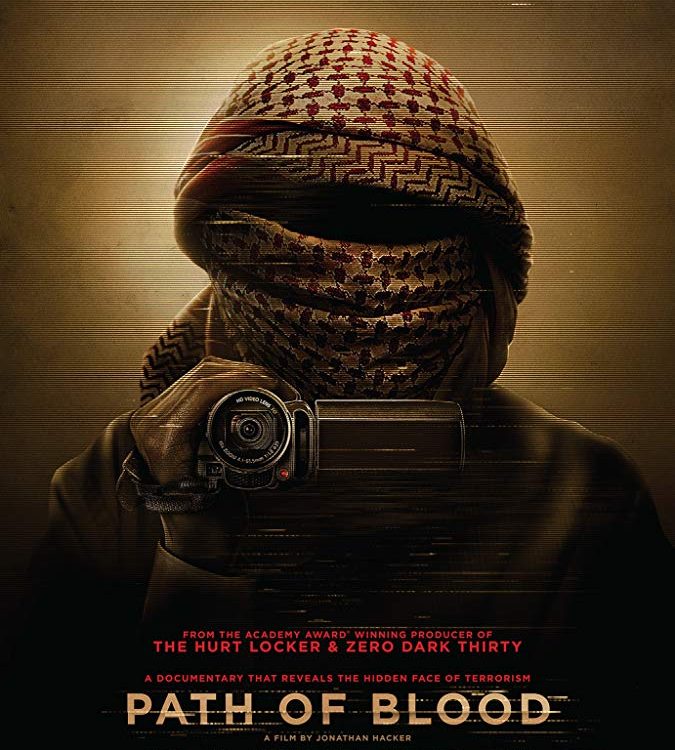

Terrorism is so often framed as an “us” vs. “them” proposition – First World being attacked by everyone else – in mainstream media outlets that it is important to be reminded that the worst impact is still being felt in the Middle East, Afghanistan, Pakistan and South-East Asia. Jonathan Hacker’s documentary, Path of Blood, is an absorbing examination of one such front line, Saudi Arabia. Drawing on over 500 hours of propaganda footage shot by Al-Qaeda cells from 2003 through 2005 that was seized by the Saudi authorities, as well as more traditional news sources, Path of Blood takes us straight into the hearts and minds of young Al-Qaeda members as well as the unwieldy efforts of the House of Saud to check the former’s campaign of terror.

The intimacy that Path of Blood largely sustains is apparent from the opening when we see cell members joke and mug for the camera while recording a grim video dispatch to the enemy. The attempts of Abdulaaziz (“Ali”), the class clown of the cell, to deliver a simple, brief call to arms illustrates how young, inexperienced and myopic the Al-Qaeda recruits are. They are like young men everywhere – keen to bond with their mates, given to horseplay and desperately seeking direction and meaning depending on the choices (or lack of) around them. During a sequence filmed at a remote training camp, we even seen them indulging in wheelbarrow races amidst the more serious business of how to shoot from a moving car or dodge sniper fire.

By contrast, the House of Saud is a remote, wealthy, but slow-moving establishment. With each bombing or attack, the government’s security forces are often left to literally pick up the pieces. They investigate and restore order, but they are also left identifying bodies and trying to make sense out of the rogue version of Islam that has emerged from within. Although the terrorism is carried out by men who have barely shaken off the growing pains of adolescence, their activities range from the crude effectiveness of suicide bombings to carefully planned assaults on oil refineries, hotels, supermarkets and the seemingly impenetrable grounds of a US consulate and the brutal kidnapping and beheading of an American engineer. While the outcomes of these actions are temporary and the casualties high on the Al-Qaeda side, the psychological impact on the House of Saud is immense.

In May 2004, Crown Price Abdoullah bin Abdulaziz gathers a meeting of leading intellectuals and religious leaders to tell them to play a greater role in educating Saudi youth about the dangers of Islamic extremism. In the same month, Al-Qaeda lays seize to a petroleum centre in Khobar where 22 people are killed and over 200 workers are taken hostage (14 of whom are killed in the battle with army and police that follows).

In the months and years to come, the back and forth between the House of Saud and Al-Qaeda continues. An amnesty is established by the government to attract some of the wavering recruits into a rehabilitation programme, but this is a war of bloody attrition. Despite the sophistication and increasing success of the state in fighting back, the documentary closes on a surreal note. Sensing a coup, Prince Muhammed bin Nayef arranges a secret meeting with a high-level Al-Qaeda leader, Ab-dulallah al-Asari, who wants to arrange a truce. Although al-Asari is searched by Nayef’s guards, he nearly kills the Prince with a bomb hidden in his rectum.

Path of Blood has the same cool just-the-facts tone of Zero Dark Thirty (Mark Boal, one of the executive producers, is a frequent collaborator with Kathryn Bigelow). The main narration by Samuel West gives us just enough details to situate who, what, where and when, but the larger contextual picture (and a why) are left to us to ponder. It is this detachment that feels as disquieting as the subject matter being shown. The filmmakers make adroit use of their materials, seamlessly edited by Peter Haddon, but more than once the violence feels aestheticised. However, as a starting point for a long overdue conversation about the role of Arab states in combating extremism, Path of Blood is exemplary documentary filmmaking and investigative journalism.

Narration by Samuel West, Tom Hollander

Executive Producers Mark Boal, Abdulrahman Alrashed and Adel Alabdulkarim

Path of Blood is in cinemas from July 13th